Level description

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void getpath()

{

char buffer[64];

unsigned int ret;

printf("input path please: "); fflush(stdout);

gets(buffer);

ret = __builtin_return_address(0);

if((ret & 0xbf000000) == 0xbf000000) {

printf("bzzzt (%p)\n", ret);

_exit(1);

}

printf("got path %s\n", buffer);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

getpath();

}

Intro

This level is similar to the previous one. Main difference is that this time, a restriction is set that prevents us to jump directly to potential shellcode we put into the buffer. We need to find a way to bypass the check at line 17 so that the program can continue executing. In this level we will learn about ret2libc attack.

Solution

Same as in previous levels, first I will lay out an idea for an approach to this problem before we can exploit stuff. For start, let’s try to make an exploit that works using GDB. The main idea is to find relevant addresses, calculate offsets, think where to store the code and finally get it to execute somehow.

I always start by finding out relevant addresses of vulnerable buffers and return addresses. By using GDB and setting a breakpoint at the getpath() function, we are able to get to the following important information:

- Using “print &buffer” we get the location of out buffer array: 0xbffffb6c

- Using “info frame” we get the location of the return address: 0xbffffbbc

- Difference between the two is: 0x50 or 80 bytes

As seen above, we calculated the number of bytes we need to write to the buffer (together with the bytes which will overflow it) to get to the return address.

Our problems begin here because the first byte of buffer’s address is 0xbf and that is exactly what will trigger the check at line 17, exiting the program. We need to somehow bypass this. To our rescue comes an interesting technique: ret2libc.

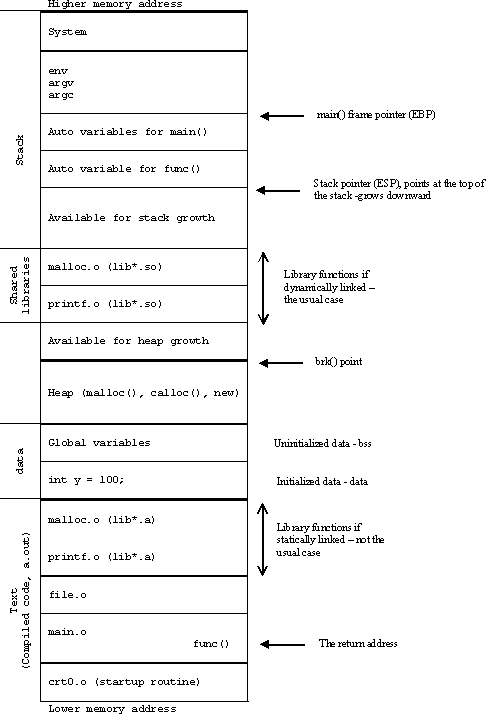

I won’t go into details about the attack because everything is already well explained in the link above, however, I will explain how is that attack applicable to our situation. The cool thing about this attack is that it allows us to redirect program execution to some other function in libc linked library which is present in memory during execution of our vulnerable program. You might ask yourself why this approach would work and the answer is simple: when redirecting execution this way, we will point to a memory location inside the library which is way towards lower memory addresses (between the heap and the stack) so our jumping location’s first byte won’t be 0xbf and therefore we will pass the check at line 17. An example program’s anatomy in memory is shown in the picture below:

To do this, we need some more information. We need an address of a function inside libc library to jump to. I decided to use the system(char *command) function as described in the linked PDF about ret2libc attack. Using GDB we can easily find that function. We can stop at the breakpoint set at getpath() function (same as before) and by issuing “print &system” we can get the address of that function.

Finding address of system() libc function

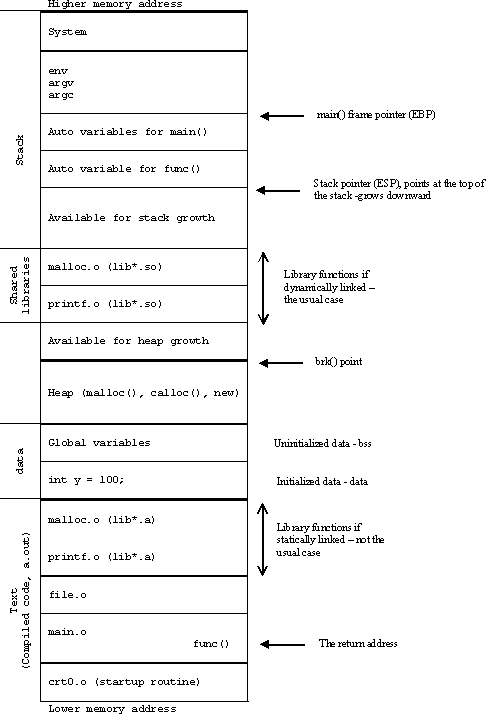

Now let’s craft our exploit. To do that we need to know how our stack looks during program execution.

Picture above shows how our stack looks during normal execution of the program. This is how the stack looks when inside the getpath() function. Now, system() function call expects one argument to be passed to it. Usually, arguments passed to functions are expected to be at address [BASE_POINTER + 8], that is directly below RET (which is at [BASE_POINTER + 4]) for our getpath() function (towards higher memory addresses). Getpath() doesn’t expect any argument so i labeled that field as “parent fun space”.We want to get shell as root so our argument will be the address to string “/bin/sh”. To make things easier, we can store that string at the beginning of the buffer so the address to our string will be the address of the buffer we found out earlier.

We need to think in advance a bit, as explained in the PDF, when the execution is redirected from our program to the system() call using RET (reminder: RET removes 4 bytes from the stack, in this case system()’s address), system() function’s prologue (push ebp; move ebp, esp) will be executed. The stack before and after the system() function call looks as shown below.

Stack before system() call:

Stack after system() call:

One important thing to note is that our “would-be getpath() arguments” is now our system()‘s return address (because it’s located after the new saved base pointer). One thing we can do is to overwrite system’s return address to point to an exit() system call so we can exit our program gracefully after we finished using our exploit. Finally, our stack needs to look like this:

We can find exit()‘s address the same way we found out system()‘s address. Our addresses are:

- exit() is at: 0xb7f2e154

- system() is at: 0xb7ecffb0

- “/bin/sh” is at: 0xbffffb6c

Ideally, our exploit would look something like this:

python -c ‘print “/bin/sh” + “\x00” + “\x90″*68 + “BBBB” + “\xb0\xff\xec\xb7” + “\x54\xe1\xf2\xb7” + “\x6c\xfb\xff\xbf”‘ | /opt/protostar/bin/stack6

Explanation: At the beginning of the buffer we will write null terminated “/bin/sh” string after which follows 68 bytes (80 – length(/bin/sh) – 1 – 4 = 68) of NOP-s (it could be any other content because we have no use for it). The “BBBB” bytes are only a marker to see if everything works as we wanted inside GDB, “BBBB” should overwrite saved EBP from getpath()‘s parent function. Next we have 0xb7ecffb0 which is system()‘s address, then we have 0xb7f2e154 which is exit()‘s address and finally we have buffer’s address 0xbffffb6c.

Using GDB we can check if it works:

First, I wrote our exploit code to “/tmp/expl” file so I could use it as user input in our program during execution in GDB. I set a breakpoint at the beginning of getpath().

As shown above, we can see that the “BBBB” marker (0x42424242) and everything else is located at expected positions. Now we can try to use this exploit directly from the terminal.

It looks like it doesn’t work as expected while exploiting it from the terminal. If we recall from the previous blog post, I said that the memory layout of the program during execution from GDB is not exactly the same as executing it directly from terminal because GDB shifts things a bit because of additional environment variables it creates. Now, I wanted to know how much of a difference is between the real addresses and the ones seen through GDB. I wrote a simple program that initializes a variable and prints its address:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void){

int i;

i = 5;

printf("Address of variable i from program: %p\n", (void *)&i);

return 0;

}

I started the program in GDB to see the address of variable i and then I did the same in terminal:

Ok, now we know that the difference between real address and GDB address is 0x30, which might not be true but at least I know the order of magnitude of shifting. Note that this change only affects the address of buffer, I’m not sure why exactly but I would say it’s because the environment is set on the stack before the variables and such and because there is plenty of unallocated memory between the stack and the linked library locations.

After playing a bit and testing out some addresses, our final address wasn’t really far away, instead of using 0xbffffb6c, the real address was 0xbffffb7c. This is it, we have root access:

NOTE: I experimented with GDB a little and saw that there was an 0x10 memory shift every time an environment variable is added or removed from GDB. I know that GDB sets 2 additional variables: LINES and COLUMNS but I don’t know where the remaining 0x30 – 0x20 = 0x10 shift comes from, I guess it might be due to program name length or something like that.

Thanks for reading!